Dr. Sacha Heath, UC Davis and Living Earth Collaborative and

Rachael Long, UCCE Farm Advisor

Codling moth spells trouble for walnut growers with larvae feeding on developing nuts, causing major yield and quality losses if left uncontrolled. Adult moths are active in the spring, have several generations per year, then go dormant during the wintertime, with larvae hibernating in protected areas, like bark crevices. During the growing season, codling moth are challenging to control because the larvae burrow inside nuts to feed, keeping them safe from natural enemies and insecticides. However, during winter months, larvae are more vulnerable to predators, offering opportunities for biocontrol by natural enemies, including insectivorous birds (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Codling moth larva cocoon eyed by a northern flicker, a predator of codling moth pests. (Image by Sacha Heath)

In apple orchards, insect-eating birds are well-known predators of codling moth, helping to reduce larval numbers by 35% to 95%, according to research over the past several decades. Our study focused on walnut orchards and the impact that insectivorous birds have on codling moth control, with two questions in mind. First, does habitat on walnut farms increase beneficial bird abundance and diversity; and second, does this lead to enhanced pest control in adjacent orchards?

To determine the potential for birds to help control codling moth, we studied bird activity in 20 different walnut orchards in the Sacramento Valley during the wintertime. Our focus was on birds that search for prey in tree bark as they travel up and down tree trunks, pecking and flaking bark with their beaks, hunting for insects. The most abundant insectivorous birds that we found in orchards with this feeding behavior included woodpeckers, flickers, oak titmouse, nuthatches, as well as families of bushtits that forage communally.

To measure the impact of bird predation on codling moth control, we obtained larvae from the USDA lab in Parlier, CA, where a colony is maintained for research purposes. The larvae were inside cocoons inside pieces of corrugated cardboard, after we forced them into dormancy by manipulating day length and temperature in growth chambers where they were reared. Armed with bags of hibernating larvae, we set out in orchards, and glued them individually on tree trunks. Some larvae were available to predators (Figure 1), others had cages over them to prevent bird predation, serving as the control group (Figure 2). Field cameras were set up to track avian predators at work.

Figure 2. Cages were placed over some codling moth larvae, preventing birds access, whereas others were open (Fig. 1) to evaluate the impact of birds on codling moth control. (Image by Sacha Heath)

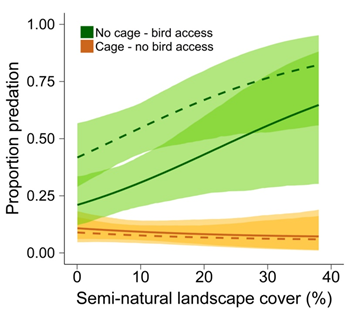

About a month later, we checked for predation and found that 46% of the uncaged codling moth larvae were eaten, while 11% of the caged larvae were eaten (by other natural enemies, such as lacewings, spiders, and parasitoid wasps), suggesting that up to 35% of predation was due to birds (Figure 3). White-breasted nuthatches and Nuttall’s woodpeckers were captured by wildlife cameras foraging on codling moth larvae on several occasions (see video link below). This reduction of codling moth larvae during the winter months by natural enemies likely helps reduce the numbers of codling moth adults during springtime flight, helping to reduce pest pressure during the growing season.

Figure 3. Predicted effects of bird exclosure cages on codling moth larval predation across a gradient of landscape cover (habitat from none to 40%) within about ¼-mi of the walnut orchards in our study. Lines indicate means, color ribbons around lines are 95% confidence intervals. Dashed lines indicate larvae on trees where at least one other larva was depredated and solid lines reflect larvae on trees where no other larvae were consumed; this differentiation helps researchers account for a birds’ ability to quickly become accustomed to novel food items (Heath and Long 2019).

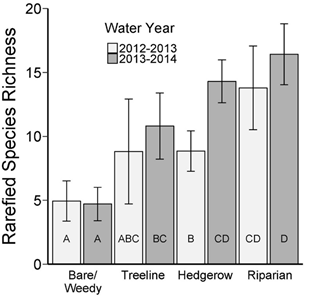

In another Sacramento Valley study among multiple crop types, we discovered that one driver behind bird abundance and diversity on farms was the presence of natural vegetation in the uncultivated crop margins, including hedgerows of shrubs, tree-lines, and remnant riparian vegetation (Figure 4). Similarly, walnut orchard margins with natural vegetation had ten times more bird codling moth predators than bare or weedy orchard margins. The more natural vegetation on and around farms, the more beneficial birds were found in the orchards, leading to better biocontrol of codling moth pests (Figure 3).

Conversely, field edge habitat does not appear to attract more pest birds. During a pilot study for this work, it was found that three of the most common avian crop pests (crows and red-winged and Brewer’s blackbirds) were detected 5 to 10 times more often in agricultural fields without hedgerows in their margins, compared to fields with hedgerows (White et al. 2012).

Figure 4. Average number of bird species in different field edge habitat types on 111 farms in the Sacramento Valley (Heath et al. 2017).

Birds forage in croplands because in many cases this is among the only remaining available habitat, especially in intensively farmed areas like the Central Valley. Increasing bird activity and pest control benefits can be achieved by planting habitat in and around farms. This includes native California shrubs like California lilac (Ceanothus), redbud, coffeeberry, toyon, coyote brush and elderberry. Field edge habitat does not appear to attract more pest birds, like starlings and blackbirds (White et al. 2013). For example, in strawberries, researchers found that bird abundance and feeding damage was lower on farms with more surrounding natural habitat, likely because the birds had somewhere else to go (Gonthier et al. 2019). Adding habitat on farms makes a difference by providing beneficial birds a safe place to forage, rest, and nest, benefiting birds and farmers.

For more information on habitat plantings on farms contact Rachael Long, rflong@ucanr.edu or 530-666-8143 or the Yolo County Resource Conservation District, pratt@yolorcd.org, 530-661-1688. We are thankful for project support from Yolo and Solano County walnut growers, who participated in this study. More information on our studies can be found at Heath and Long 2019 and Heath et al. 2017.

Watch a video of Nuttall’s woodpecker eating our experimental codling moth larvae in a walnut orchard: Insect-eating bird video (Video by Sacha Heath).

Leave a Reply